On a Different Type of Generational Wealth

Yesterday, at my town’s Fourth of July art and craft fair, I manned an informational booth about SPARE to share what I’m building and how the community can help.

Over eight hours, I spoke to dozens of people. Many were curious about SPARE and eager to share stories—mostly about loved ones who’ve passed and the legacy they left behind in the form of, well, a whole lot of “crap.” Of course, they don’t see it as crap—they see it as overwhelming. They adored their parent or spouse and can’t bear to part with the things they used to create. But they also have no idea where to take it—and they definitely don’t want to throw it out.

I’m 100% an introvert. I always have been. It wasn’t until after COVID, when we all had time to sit with ourselves, that I realized how much ignoring that assessment had contributed to years of social anxiety. Like Kenny Rogers says, “you got to know when to fold ’em…” To me, that means stepping away when I know I’m drained. It’s awkward, but we’ll have friends over for dinner and, a few hours in, I’ll hit my limit, explain how I’m feeling, say goodnight, and head to my room. At my own house. When we’re hosting. Thankfully, my husband usually has a few more hours in him and gets to be the functional half of our coupling.

I am drained by social interaction and talking—even though I almost never stop talking. That’s the surprisingly contradictory nature of introversion: you can be outgoing and still be completely knocked out by social interaction.

So yeah, eight hours at a booth should have been a complete nightmare.

But it wasn’t.

When I’m passionate about something, I’m all in—at eleven. And when it comes to one of the things I care most deeply about—the people behind the materials donated to SPARE—I’m completely swept up in the mission. The stories. The legacies. (The Legacy in Sebastopol clearly isn’t just a random name) It’s a lot, in the best way. So much so that I can speak about it for eight hours straight and still be moved to tears—more times than I’d like to admit.

I don’t think people know what to make of me, but I do think that they definitely know that is what I should be doing.

And this is why one of the first pages I added to sparecrafts.org was a place to collect the stories behind what people donate. Submissions can be a sentence or a few paragraphs—whatever feels right. Just something about who it belonged to or how it was used. That kind of context matters. It helps people see the person behind the materials, not just the stuff. Maybe it was part of a daily routine, a short-lived hobby, or a whole creative life. It doesn't need to be polished. A photo is great too, especially if it shows the person or something they made. This shop is being built from what people leave behind, and these stories help show why that matters.

If you’re donating something to SPARE and there’s a story behind it, I’d really love to hear it and possibly share it somewhere in the shop. And if not, that’s okay— I’ll probably imagine one anyway.

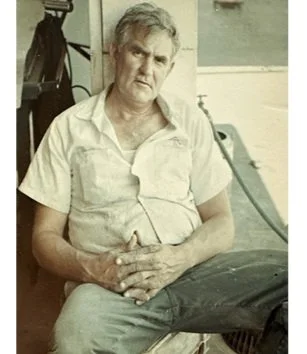

Here’s one that I’d write, and perhaps I’ll put it on display next to his can of pencils and pens that I took after he passed away.

•••

My grandfather (Dooley, as I inexplicably called him) — as long as I knew him — was always making. He didn’t have formal training, and like so many others of his generation, he had to take on adult responsibilities far too young. A child of the Depression, at age twelve, he started driving a tow truck in the Cleveland winters and joined the family’s autobody busines. He was practical and expected not to show emotion. In the first two-thirds of his life, he did indeed show a lot of emotion, but not in a good way — thankfully, he mostly exorcised those demons before I came around.

We lived in a multigenerational household, so my grandparents were my caregivers. My grandmother cooked, played the piano and sewed, while Dooley … made some really weird things. He seemed to spend most of his waking life in our garage making something. Our house was a bit Addams' Familyish, with taxidermied animals of prey next to gothic statues of Saints behind glass. Dooley loved working with metal and that meant that we ate our meals next to a seven foot floral sculpture in our kitchen dining space. He’d carve and paint wooden ducks, replicate Early Cycladic figurines and even use plaster to make replica fossilized fish slabs. He mimicked Rothko on seven foot canvases and highly toxic automotive paint. My constant runny nose induced by the paint’s VOCs kind of became “my thing.”

It really was a great childhood!

Late in life, he started small metal sculptures from materials we all toss away. Butterflies, bugs, and flowers crafted from old tin cans. And, whenever I would come — as an adult — to visit them, the end of the trip always ended with him loading a box of his creations into our car.

Clearly, seeing this act of creating — watching a jack of all art trades — was one of, if not the most, pivotal influence in shaping who I am.